2024 Tour de France Route

The 2024 route features four mountain-top finishes, two time trials, and 34 kilometers of cobblestone sections, offering a course that is both challenging and balanced, starting in Italy and ending in Nice. Due to the Paris Olympics next year, the race finish has been moved from Paris to Nice.

Since the inception of the Tour de France in 1903, the men’s race has always concluded in Paris or its surrounding suburbs, and since 1975, it has consistently finished on the Champs-Élysées.

Here is a summary of the 2024 Tour de France route:

- Total Distance: 3492 kilometers

- Number of Stages: 21

- Duration: From June 29 to July 21

- Countries Visited: Italy, San Marino, France, and Monaco

- Mountain Stages: 7 high mountain stages

- Summit Finishes: 4

- Cobblestone Sections: 32 kilometers

- Start Location: The race starts in Italy, marking the first time in its history.

This route promises a diverse and challenging course for the cyclists, with a historic start in Italy and the traditional finish in France, deviating from Paris for the first time in favor of Nice due to the Paris Olympics.

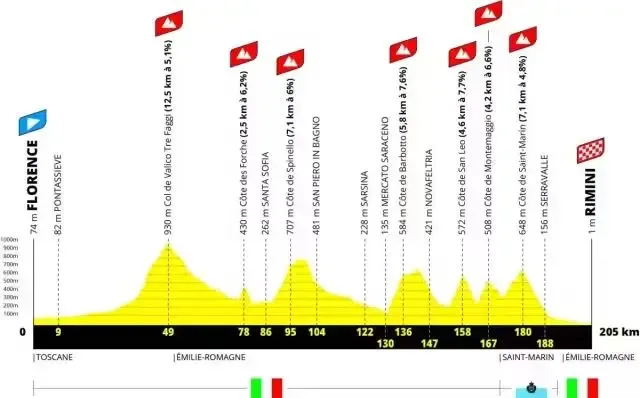

- On the 100th anniversary of an Italian cyclist’s first victory at the Tour de France and the 70th anniversary of the race’s first overseas start, Italy becomes the 11th country to host the start of the Tour de France outside of France. Cyclists embark on the journey of the 111th edition of the Tour de France from the home of Gino Bartali in Florence. Although there are no high mountain obstacles, the course, which exceeds 200km in distance and 3600m in elevation gain, is more difficult than this year’s stage, making it the most challenging opening stage in the history of the Tour de France. Among the numerous climbs along the route, the most critical is the ascent through San Marino (the 13th overseas country visited by the Tour de France).

- Setting off from Cesenatico, the hometown of another Italian legend, Marco Pantani, the race passes through Faenza (the headquarters of the Trek-Segafredo team, formerly known as the Red Bull team) and Imola but circumvents the mountains. Among these, the Gaiarine climb was a key ascent in the 2020 UCI Road World Championships held temporarily. Will the Shanghai-born cyclists rise to the occasion here? As the race approaches Bologna and enters the mountains for laps, especially the final two climbs up San Luca, which are the most critical. Just like last year, the first two stages are ones where the general classification (GC) riders cannot afford to relax, but in the end, it might be a climber who is less closely watched that could launch a surprise attack to win the stage and the yellow jersey.

- Despite its considerable length of 229km (the longest of this edition) and minor undulations, the stage connecting the two largest cities along the Po River—Piacenza and Turin—finally offers sprinters a chance to shine. Turin also becomes the first city in history to host the grand departures of two Grand Tours in the same year. With the preceding stages taking their toll and the high mountains to follow, one can imagine the level of tedium this stage might bring.

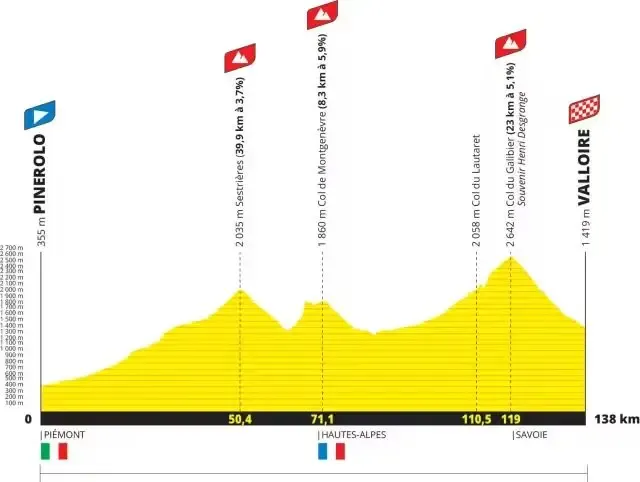

- The most recent Italian city to host a stage of the Tour de France, Pinerolo (in 2011), once again serves as the starting point. Although, like that stage, the HC triple play is a bit early for the first week of the Tour, taking the shortcut over the Côte de Sestrière and Mont Génevière to ascend the Col du Galibier is still extremely challenging for the 4th stage, marking the earliest appearance of the super climbs in the Tour de France. Valloire, next to the Télégraphe mountain, has only served as the finish of the Tour de France in 1972 and 2019, both times after descending from the southern slopes of the Galibier. The winner of these two editions, Eddy Merckx, goes without saying, but the still-active Chief (a nickname for a prominent cyclist) having to watch from the sidelines is a poignant reminder of the passage of time.

- After a day trip, the riders bid farewell to the Alps, and the race will not encounter the dramatic landslides as it did the last time it started from Saint-Gervais-les-Bains. Following the “episode” of the previous day, the sprinters are back on the job.

- Unlike Macon, which only started hosting the Tour de France start this century, the “heart of Burgundy,” Dijon, last served as the finish of the Tour de France in 1997 during a dramatic stage. At that time, during a one-on-one sprint, Voskamp and Hampstaedt collided head-on and were both penalized, leading to Traversoni winning the stage in a small group sprint. Sprinters and their lead-out men should learn from the lessons of history and be mindful of their movements before the finish line.

- The 25-kilometer individual time trial (ITT) weaves through the vineyards of the Côte d’Or, featuring a middle section that includes a 1.6-kilometer climb with a gradient of 6.1%. Does this mean that nowadays, only riders with excellent climbing abilities are worthy of winning the Tour de France’s ITT stages?

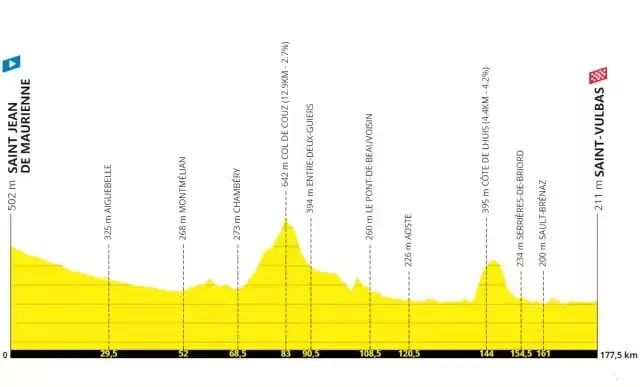

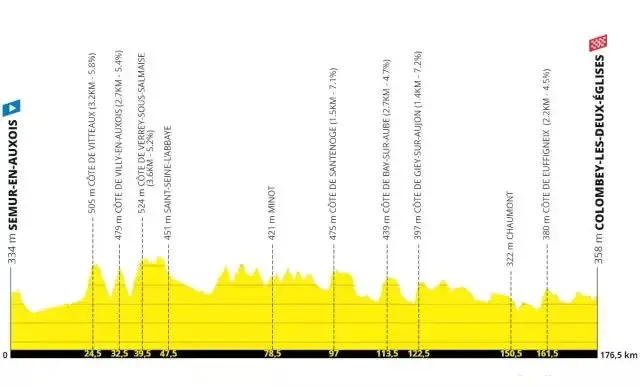

- Despite the continuous minor undulations throughout the course, the sprint teams should be able to manage the situation and then compete for the fastest speed. The finish line at Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, although making its first appearance in the Tour de France, is a place where a great man rests. In 1934, General de Gaulle purchased a villa here. Since then, except for the years of unyielding struggle in Africa, this place has been both a holiday resort when in high position and a retreat when away from the court, and he was eventually buried here. The French team and sprinters should have an extra motivation to pay tribute to him.

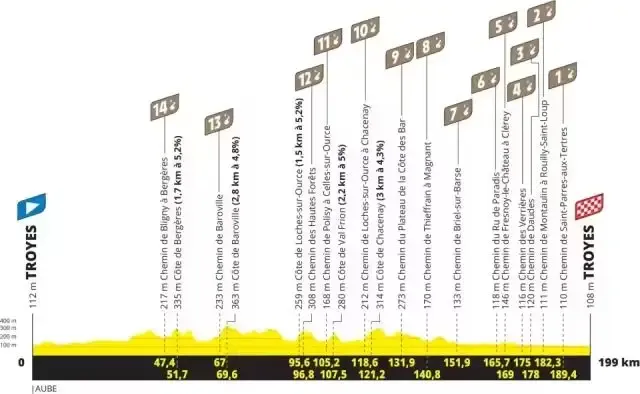

- On the last day of the first week, it’s a trip to the countryside of Troyes! The modern Tour de France finally welcomes its first dirt road stage in this edition, with a total of 14 sections of dirt road amounting to 32 kilometers, and some steep sections in the first half of the stage, which can be considered a rather aggressive setup. If the Dragon King could come to watch the race, the excitement would be multiplied.

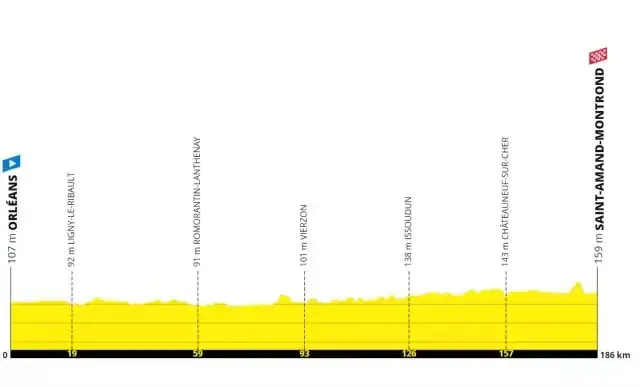

- After a day of rest in Orleans, the cyclists continue their journey. Although the route is extremely flat, they must not be complacent. The last time the Tour de France visited Saint-Amand-Montrond (in 2013), crosswinds shattered the peloton. “Ba Shen,” who was second in the general classification, suffered a puncture at an unfortunate time and lost nearly 10 minutes in that stage, dropping out of the top ten. The winner of that stage is still chasing the record, while the younger runner-up has sadly left the road cycling scene, and a newcomer will take over his “second brother’s” throne.

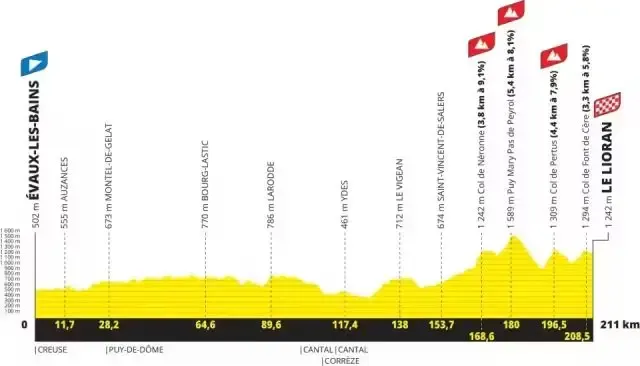

- This is a very interesting Central Massif stage, where the last 50 kilometers feature steep but not very long climbs such as the Monts Nénéron, the Marie-Blanche (the finish of Stage 13 in 2020, where the pineapple tactic was first hinted at), and the Puy de Dôme. However, these are still some distance from the finish line. The only previous time the Tour de France visited Le Riou was in the last normal Olympic year, and the stage winner then also became an Olympic champion. Such a high-caliber stage is worth the effort of all the top riders to fight for it. After all, this is the only mountain stage within 10 days, and it is appropriate for the GC contenders to test each other.

- The first half of the stage is quite undulating, while the second half is relatively flat. On the two previous occasions when the Tour de France visited the city of Villeneuve-sur-Lot, the stages had a similar profile, and both ended with a breakaway “rabbit” (early attacker) securing the victory.

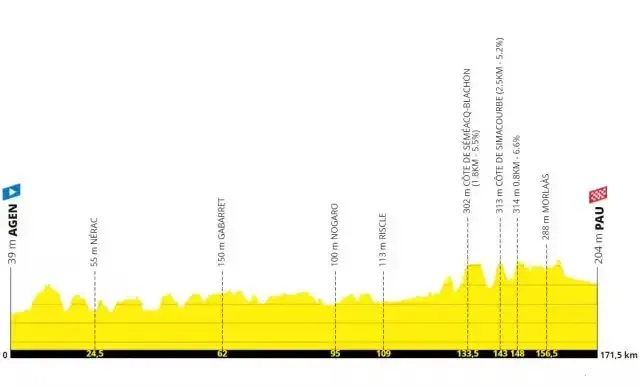

- The last time Pau served as the finish line for a stage of the Tour de France in a mass-start format was back in 2018, when Demare outperformed the rising star Alaphilippe to claim the victory. These two riders also happen to be the most recent French cyclists to have won a stage of the Tour de France in sprint finishes.

- It feels like the Tour de France has almost forgotten about the general classification (GC) riders until reaching the Pyrenees. The first half of the stage takes the peloton from Pau into the mountains, then to the Tourmalet, a heavyweight climb for both the Tour and the Vuelta this year (this time ascending from the west side, the same direction as in the Vuelta). Following this, there’s a return to the Hautacam, which is not too difficult, and finally, the first mountain-top finish (MTF) of this Tour, the Pla d’Adet. When it was first used in 1974, 38-year-old Poulidor won the last stage of his career at the Tour de France. However, 50 years later, his grandson will find it hard to replicate his ancestor’s glory here. Fans are hoping that the GC riders will engage in fierce battles on the Tourmalet, as they did this year; anything less would be impolite to the spirit of the race.

- Although each climb is challenging and the total elevation gain is close to 5000 meters, the highest of this edition, they are not concentrated, and it is likely that the general classification riders will have a decisive battle on the Plateau de Beille, which may not be what the organizing committee wants to see on Bastille Day. Compared to the previous two visits here where a breakaway rider won and the GC contenders were quite peaceful, duels such as Rasmussen vs. Contador or Armstrong vs. Basso would have increased viewership (unfortunately, these are now content that TV stations are not allowed to broadcast). The finish line had newly built wooden structures that wanted to make an appearance through the Tour, but it turns out they will only be repaired by the end of the year. The efficiency is really worth making fun of.

- The first day of the third week is also the last chance for sprinters in this edition of the race, coincidentally reversing the start and finish points of Stage 2 of the 2017 Vuelta a España. The ancient city of Nîmes is not uncommon in recent Tours de France, and even going back a full four Olympic cycles, a young Bradley Wiggins began his career here. The lower Rhône River area is also a classic area prone to crosswinds, so paying attention to the wind direction and positioning is crucial.

- After two weeks on the road, the cyclists have finally returned to the Alps. Compared to the climb before the finish line, the Col de la Forclaz, earlier in the stage, offers a better opportunity for the general classification (GC) riders to show their prowess.

- The hilly stage deep into the Alps seems almost certain to end in a breakaway victory. It’s hard to imagine that a team with pure sprinters would risk their lives to control the race. Although the finish line at Barcelonnette is making its debut as a stage finish in the Tour de France, it holds a special historical significance in the race. In 1975, it made its first appearance as the starting point of the Tour. The day before, Thevenet took advantage of Merckx’s injury from an intimate contact with the audience the day before, and took over the yellow jersey from him. He made his first appearance in the yellow jersey here, marking the beginning of the “post-Merckx” era of the Tour de France.

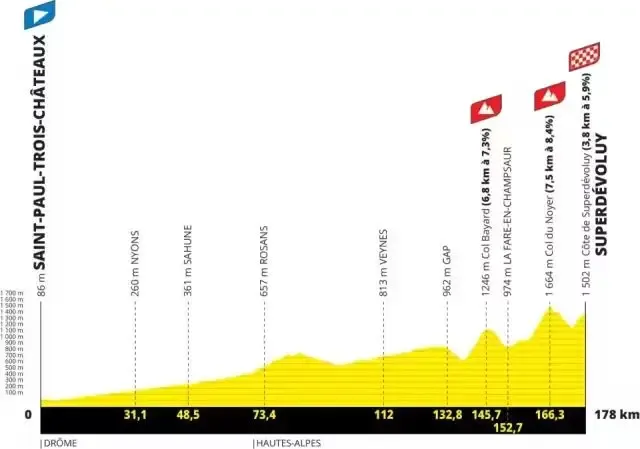

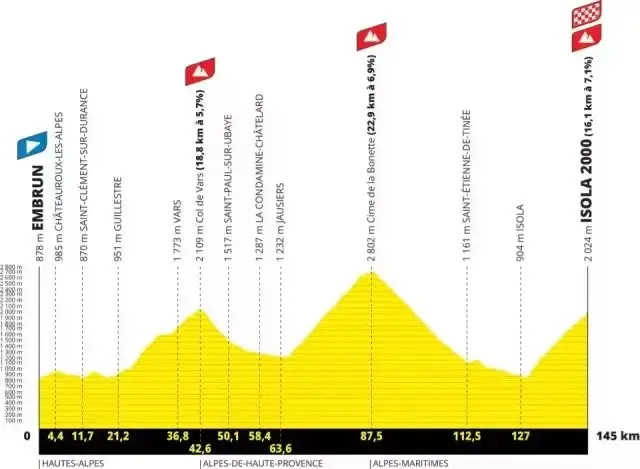

After enjoying the beautiful scenery of the Serre Poncon Lake the day before, the general classification riders start their ranking sprint in the Tour de France from the dam’s tail at Embrun. The finish of the stage that last started from here was exactly the Valloire that the riders have already checked in two weeks ago. After warming up at the Col du Vars, the riders will challenge the highest point of this year’s Tour de France, the Col du Galibier. Although the altitude of 2802m is only comparable to the city area of Golmud, let alone competing with the various entrances to Tibet, this is already the highest pass in Europe that cars can pass. It is hard to imagine that the GC can be peaceful here. The first two times the Tour de France passed through here were both the Spanish first Tour de France champion, Bahamontes. This summer, he passed away at the age of 95, and his soul flew to the mountains he had conquered. The last time the Tour de France passed by, there was also a dangerous situation of the car being destroyed and people falling, which shows that the downhill is also very dangerous, and you must not be careless. The final Isola 2000 was only visited once by the Tour de France in 1993, and Rominger won over Indurain, but the final GC ranking was just the opposite. Three climbs with an altitude of more than two thousand meters are a huge test for riders who are not used to high altitude.

-

The GC riders will no longer be able to recover as leisurely as they did after the high-altitude ordeal of Stage 4; what follows is still a high-difficulty mountain stage. Although the altitude is not as daunting as the day before, the total amount of climbing has not decreased but increased. In addition to the opening Col de la Brossette, since 2017, the Côte de la Croix de Ceyreste, Tournon, and Col de la Coreme have successively become the first mountaintop finishes of the daily stages, and then alternately used. This time they appear together on the Tour de France as the last mountain stage, which can be called the “Nice Circuit Race pro max plus.” However, it is still the often-mentioned question - will the GC riders really take the mountain stage before the TT seriously? This stage will also be used for the Tour de France Challenge, and if you are interested, you can sign up to experience it.

-

Due to the Olympics, this century-old race will conclude for the first time not on the Île-de-France. For many top riders, Monaco is like coming home, and this stage, like the previous one, is a route they often ride in their daily training. However, their true capabilities will be determined by the stopwatch. The climb of the Col d’Eze and the descent make the short 33km individual time trial (ITT) have an elevation gain of 700m. Given the surprising plots of the ITTs in recent years of the Tour de France, this final battle is full of suspense. The last time the Tour de France ended with an ITT, an 8-second gap became an insurmountable moat for the French to this day. If the competition is more intense this time, Nice will be forever engraved in the annals of history.